A Power of Their Own

Ozarks Electric’s founders created a connection that still serves us today.

By Amy Merck, Editor

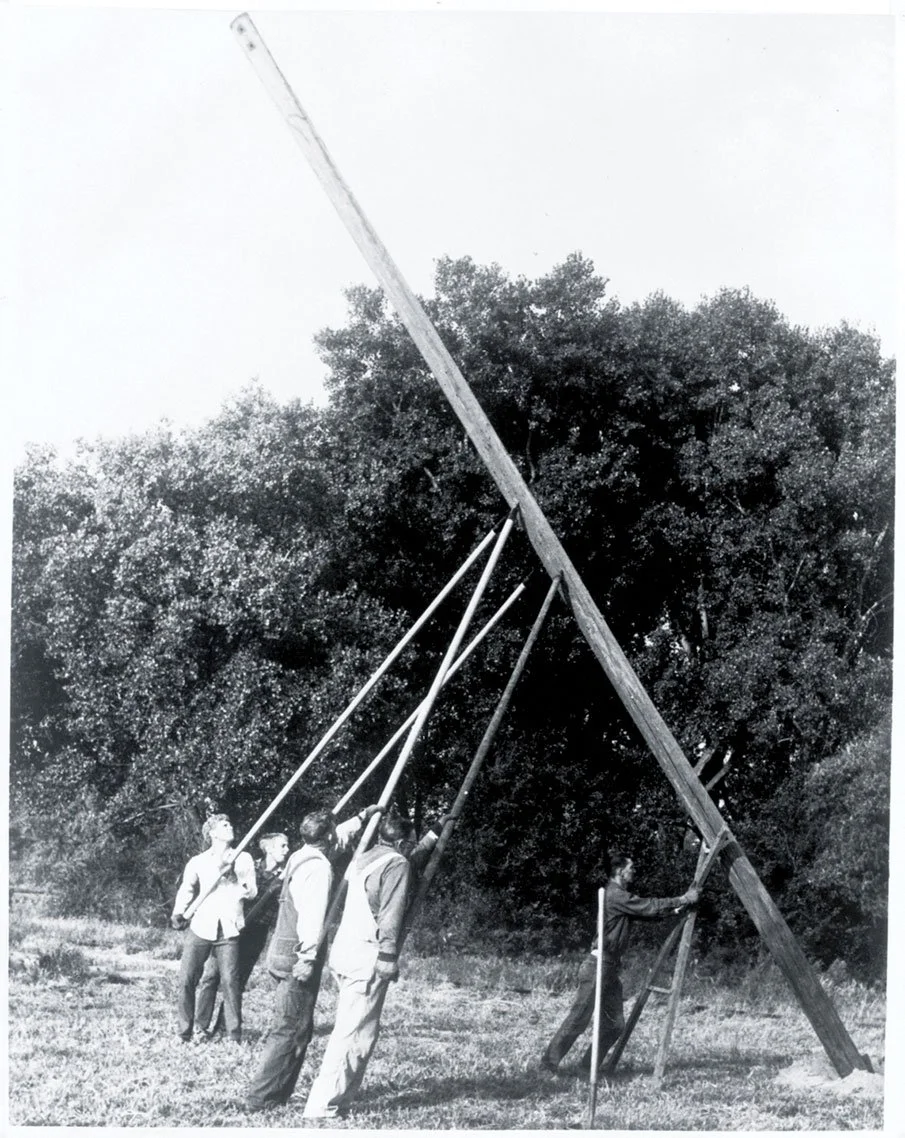

A right-of-way crew works north of Westville, Okla., in the 1940s. (Ozarks Electric archives.)

Memo and Rose Morsani got their hopes up when the rumors didn’t die down. They had been waiting and working in Tontitown for years, helping businesses and neighbors and hoping for change. This time, it might be their turn. They might finally get electricity.

It was 1938, and farmers across Northwest Arkansas were still recovering from the twin hardships of the

Great Depression and years of drought. Congress had passed the Rural Electrification Act (REA) of 1936 to bring power to the millions of Americans still living without it. But electricity wouldn’t simply arrive. Rural residents would have to organize, borrow the funds and build the lines themselves.

Darkness and Determination

Memo Morsani was a child when he came to Northwest Arkansas in 1898 with his father and about 40 other Italian families. The hills and climate reminded them of their northern Italy, so they planted what they knew best: grapes. But even a familiar crop required relentless work. Every task of farm life — hauling water, hand-scrubbing clothes, cooking, cultivating — demanded daylight and muscle.

By 1930, only 2.1 percent of Arkansas farms had electricity, according to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture. Fayetteville, by contrast, had electricity as early as 1888. Just a few miles from their fields, shop windows glowed after dark, students studied by electric light and water poured from faucets to fill pots and washing machines.

Without electricity, rural life stayed limited by the hours of available sunlight and manpower. Farmers couldn’t mechanize to save time or increase yield, and small communities couldn’t attract stores, industry or doctors. The cycle fed itself: no power meant no growth, and no growth meant no power.

Even after Congress passed the REA, large for-profit utilities refused to extend lines where profits were thin. The countryside, they decided, wasn’t worth the cost.

The members of the new co-op were often the same ones who built the lines. (National Archives.)

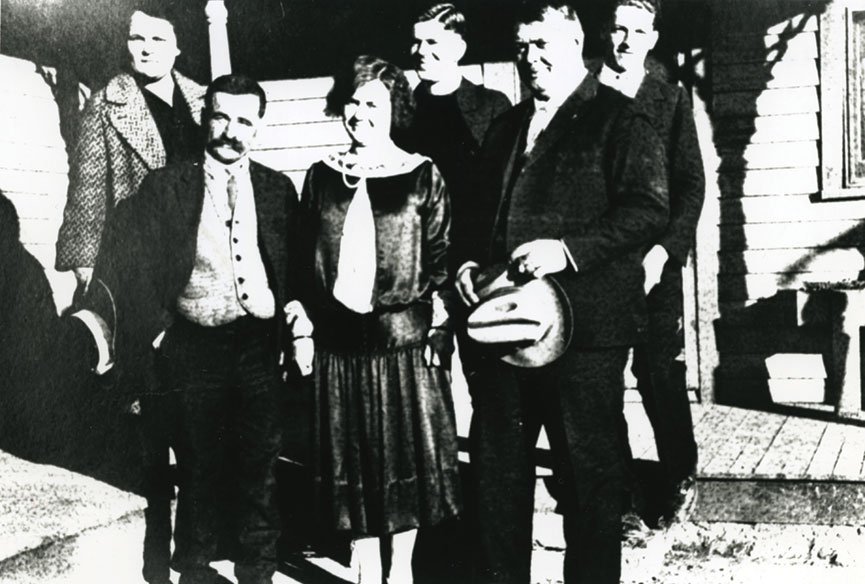

The Morsanis on their wedding day, Dec. 29, 1927, with, from left: Mary Bastianelli, Frank Baudino, Rose Bastienelli Morsani, Father John Francis McBaron, Memo Morsani and Amerigo Morsani. (James Riley Tessaro Collection, Tontitown Historical Museum.)

Neighbors Organize

The people of Northwest Arkansas disagreed. Their solution would come in the form of an electric cooperative – owned by members, not investors – where they work together to build their own power lines. They needed to sign up four members for every mile of line.

So they organized meetings, knocked on doors and walked fence rows with neighbors to identify future pole locations. Memo and Rose Morsani were community leaders who spoke both English and Italian, and they volunteered to translate details about the cooperative to Tontitown’s Italian families, helping turn skepticism into vital signatures for the co-op.

Their pitch was simple: pay a $5 membership fee to join the new cooperative and commit to spending $2.50 a month on electricity. In return, each member would be a co-owner of the cooperative and have a voice in how it was run.

The first organizing meeting, led by Edna Henbest on May 30, 1938, at the Mount Comfort Community House, enrolled 20 households. Within months, they met their membership goal. The new Ozarks Rural Electric Cooperative was approved for an REA loan of $244,000 to build 260 miles of line to provide electricity to about 1,500 homes, business, schools and churches in Washington, Madison and Benton counties.

Bringing the Light

Building those first lines was as demanding as the years that led to them. Many of the workers were co-op members, given first preference for the jobs that would bring light to their own homes. Mules hauled poles and hardware where trucks couldn’t go. Men dug holes by hand and pulled poles upright with ropes.

Their effort paid off on May 10, 1939, when the home of Samuel and Juanita Cantrell of Tontitown — who had sold the co-op a small plot of land for its first substation for $2 — was the first to receive electricity. Tontitown, Harmon, Elm Springs, Stony Point, Wheeler, Mount Comfort and Meadow Valley were all part of the first 85 miles of line to be energized. Construction in Oklahoma began the next year, extending service into Adair and Cherokee counties.

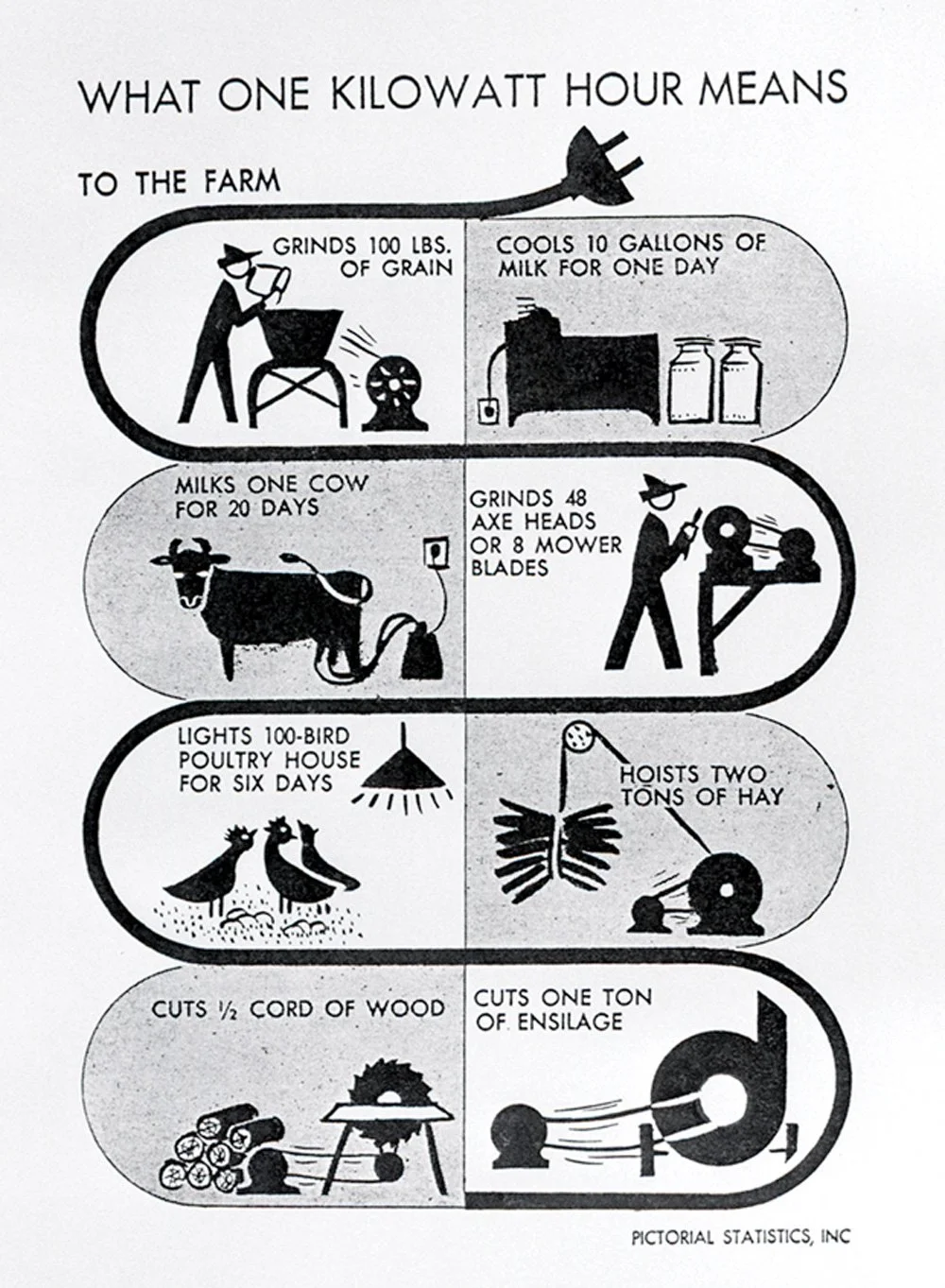

For the Morsanis and other co-op pioneers, electricity transformed everyday life. It brought refrigeration, milking machines, feeders and water pumps to farms. Improvements such as electric incubators helped propel the entire region’s thriving poultry industry.

Ozarks Electric Cooperative — “Rural” was dropped from the name in 1962 — was the 11th electric cooperative formed in Arkansas. Today, 17 co-ops operate in the state, and electric cooperatives nationwide serve more than 42 million people, according to the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association.

Ozarks Electric’s office employees in 1946. (Ozarks Electric archives.)

A 1930s-era educational poster highlights how electricity can aid in life on a farm. (National Archives.)

The Power Endures

Ozarks Electric’s story didn’t end when the lights came on. The cooperative now serves 92,000 meters and continues to modernize, adding substations in growing communities and using GPS to map lines, automated meters to track usage and technology to monitor the grid in real time.

“Staying ahead of technology isn’t optional,” said CEO Mitchell Johnson. “The tools may be more advanced today, but they help us fulfill our purpose of making life better, safer and more connected for our members.”

That commitment led Ozarks to launch telecommunications subsidiary OzarksGo in 2016. Fiber internet now connects homes, schools and businesses across both rural areas and fast-growing cities. More than 7,000 miles of fiber have been installed in less than a decade.

Yesterday, progress was a single light bulb in a barn. Today, it’s broadband and real-time monitoring. Tomorrow, progress will look different again. But just like our founders, Ozarks Electric will be there to build it and make sure it reaches everyone.

An Ozarks Electric right-of-way crew in 1956. (Ozarks Electric archives.)